http://www.shoulderdoc.co.uk/

What is it?

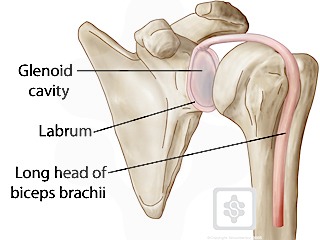

The shoulder is a ball-and-socket type of joint and is anatomically referred to as the gleno-humeral joint, describing the two bony structures involved. The socket is the glenoid cavity, a cup-shaped piece of bone that juts out from a corner of the shoulder blade (scapula). The rim of the glenoid is formed by cartilage called the labrum. The ball that fits into the socket is the head (upper part) of the humerus (arm bone).

The upper (superior) part of the labrum anchors one of the two tendons of the biceps muscle . The feature that makes SLAP possible is the way the upper biceps tendon hooks over the head of the humerus. If the arm is forcefully bent inward and twists at the shoulder, thehumeral head acts as a lever and tears the biceps tendon and labrum cartilage from theglenoid bone in a front-to-back (anterior-posterior) direction. And that is how the name SLAP is derived - Superior Labrum Anterior-Posterior or, in plain English, Upper Rim Front-Back.

SLAP area and SLAP Lesion - pull-off of the Biceps origin (superior labrum) from the Glenoid.

Causes and Risk Factors

Often an initial forceful movement of the labrum attached to the biceps tendon to be torn away from the bone (glenoid). This may be associated with a Dislocation of the joint, but commonly occurs in sportsmen with a pull on the arm, weightlifting, throwing injury or tackle. If the initial condition does not heal properly, pain will result and worsen over time.

Often an initial forceful movement of the labrum attached to the biceps tendon to be torn away from the bone (glenoid). This may be associated with a Dislocation of the joint, but commonly occurs in sportsmen with a pull on the arm, weightlifting, throwing injury or tackle. If the initial condition does not heal properly, pain will result and worsen over time.

The typical symptoms are pain at the top of the shoulder, clicking and pain with overhead activities. These may be confused with AC Joint problems , but athletes with SLAP tears have pain with eccentric biceps loading (such as going down in a bench press). AC Joint pain is usually felt when pressing out at the end of a shoulder or bench press.

Risk Factors: Overhead and contact sports pose a greater risk of labral tears (SLAP lesions).

Types of SLAP Tears - Depending on the type and severity of injury, the labrum will tear in different ways and degrees. These are classified as a guide to treatment. Click Here to see the Types of SLAP Tears

Types of SLAP Tears

Authors: Lennard Funk

If you have been diagnosed with a SLAP tear, your surgeon may have called it a 'Type 1 or 2 or 3, etc'. SLAP tears have been classified according to their severity of tear. Please note that it does not mean that the outcome of surgery is worse, it just gives us surgeons a guide to management and a form of communication. The common types are types 1 to 4. There are other types, but these are rare.

SLAP Type 1

This is a partial tear and degeneration to the superior labrum, where the edges are rough and fray along the free margin, but the labrum is not completely detached.

Treatment is usually to 'debride' (clean) the edges.

SLAP Type 2

Type 2 is the comonest type of SLAP tear. The superior labrum is completely torn off the glenoid, due to an injury (often a shoulder dislocation). This type leaves a gap between the articular cartilage and the labral attachment to the bone. Type 2 SLAP tears can be further subdivided into (a) anterior (b) posterior, and (c) combined anterior-posterior lesions.

Treatment is reattachment of the labrum (SLAP repair). This is done arthroscopically(keyhole) using suture anchors.

SLAP Type 3

A Type 3 tear is a 'bucket-handle' tear of the labrum, where the torn labrum hangs into the joint and causes symptoms of 'locking' and 'popping' or 'clunking'.

Treatment usually involves removal of the 'bucket-handle' segment and then repair of any remaining detached, unstable labrum (SLAP repair). This is done arthroscopically (keyhole) using suture anchors.

SLAP Type 4

The Type 4 SLAP tear is one where the tear of the labrum extends into the long head of bicepstendon.

Treatment is reattachment of the labrum (SLAP repair) and repair of the biceps tear, or abiceps tenodesis. This is done arthroscopically (keyhole) using suture anchors.

For more information, please see the Education Section

Treatment

Painkillers and anti-inflammatories - help control the pain

Painkillers and anti-inflammatories - help control the pain

Surgery is recommended if an athlete wants to continue their sports and training - SLAP lesions are repaired by keyhole surgery (arthroscopically) through 2 or 3 small incisions. Some SLAP lesions can be simply debrided and cleaned, whilst most need repairing depending on the severity of the lesion. The associated lesions are also treated such as labrum and ligament lesions with Instability.

For more details of the Surgery CLICK HERE

Prevention

Strong shoulder muscles remain the best defence against shoulder injuries. Exercises that build up these muscles around the shoulder should be done. Adequate warm-up before activity and avoidance of high-contact sports will help prevent of an instability-causing injury.

Strong shoulder muscles remain the best defence against shoulder injuries. Exercises that build up these muscles around the shoulder should be done. Adequate warm-up before activity and avoidance of high-contact sports will help prevent of an instability-causing injury.