Dementia, a syndrome with many causes, affects >4 million Americans and results in a total health care cost of >$100 billion annually. It is defined as an acquired deterioration in cognitive abilities that impairs the successful performance of activities of daily living. Memory is the most common cognitive ability lost with dementia; 10% of persons >70 and 20–40% of individuals >85 have clinically identifiable memory loss. In addition to memory, other mental faculties are also affected in dementia; these include language, visuospatial ability, calculation, judgment, and problem solving. Neuropsychiatric and social deficits also develop in many dementia syndromes, resulting in depression, withdrawal, hallucinations, delusions, agitation, insomnia, and disinhibition. The most common forms of dementia are progressive, but some dementing illnesses are static and unchanging or fluctuate dramatically from day to day. Most diagnoses of dementia require some sort of memory deficit, although there are many dementias, such as frontotemporal dementia, where memory loss is not a presenting feature. Memory and executive function are discussed in Chap. e6.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY OF THE DEMENTIAS

Dementia results from the disruption of cerebral neuronal circuits; the quantity of neuronal loss and the location of affected regions are factorsthat combine to cause the specific disorder .Behavior and mood are modulated by noradrenergic, serotonergic, and dopaminergic pathways, while acetylcholine seems to be particularly important for memory. Therefore, the loss of cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) may underlie the memory impairment, while in patients with non-AD dementias, the loss of serotonergic and glutaminergic neurons causes primarily behavioral symptoms, leaving memory relatively spared. Neurotrophins (Chap. 360) are also postulated to play a role in memory function, in part by preserving cholinergic neurons, and therefore represent a pharmacologic pathway toward slowing or reversing the effects of AD.

Dementias have anatomically specific patterns of neuronal degeneration that dictate the clinical symptomatology. AD begins in the entorhinal cortex, spreads to the hippocampus, and then moves to posterior temporal and parietal neocortex, eventually causing a relatively diffuse degeneration throughout the cerebral cortex. Multi-infarct dementia is associated with focal damage in a random patchwork of cortical regions. Diffuse white matter damage may disrupt intracerebral connections and cause dementia syndromes similar to those associated with leukodystrophies, multiple sclerosis, and Binswanger’s disease (see below). Subcortical structures, including the caudate, putamen, thalamus, and substantia nigra, also modulate cognition and behavior in ways that are not yet well understood. The effect that these patterns of cortical degeneration have on disease symptomatology is clear: AD primarily presents as memory loss and is often associated with aphasia or other disturbances of language. In contrast, patients with frontal lobe or subcortical dementias such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD) or Huntington’s disease (HD) are less likely to begin with memory problems and more likely to have difficulties with attention, judgment, awareness, and behavior.

Lesions of specific cortical-subcortical pathways have equally specific effects on behavior. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has connections with dorsolateral caudate, globus pallidus, and thalamus.

Lesions of these pathways result in poor organization and planning, decreased cognitive flexibility, and impaired judgment. The lateral orbital frontal cortex connects with the ventromedial caudate, globus pallidus, and thalamus. Lesions of these connections cause irritability, impulsiveness, and distractibility. The anterior cingulate cortex connects with the nucleus accumbens, globus pallidus, and thalamus. Interruption of these connections produces apathy and poverty of speech or even akinetic mutism.

The single strongest risk factor for dementia is increasing age. The prevalence of disabling memory loss increases with each decade over age 50 and is associated most often with the microscopic changes of AD at autopsy. Slow accumulation of mutations in neuronal mitochondria is also hypothesized to contribute to the increasing prevalence of dementia with age. Yet some centenarians have intact memory function and no evidence of clinically significant dementia. Whether dementia is an inevitable consequence of normal human aging remains controversial.

THE CAUSES OF DEMENTIA

The many causes of dementia are listed in Table 365-1. The frequency of each condition depends on the age group under study, the access of the group to medical care, the country of origin, and perhaps racial or ethnic background. AD is the most common cause of dementia in Western countries, representing more than half of demented patients. Vascular disease is the second most common cause of dementia in the United States, representing 10–20%. In populations with limited access to medical care, where vascular risk factors are undertreated, the prevalence of vascular dementia can be much higher. Dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the next most common category, and in many instances these patients suffer from dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). In patients under the age of 60, FTD rivals AD as the most common cause of dementia. Chronic intoxications, including those resulting from alcohol and prescription drugs, are an important and often treatable cause of dementia. Other disorders listed in the table are uncommon but important because many are reversible. The classification of dementing illnesses into two broad groups of reversible and irreversible disorders is a useful approach to the differential diagnosis of dementia.

In a study of 1000 persons attending a memory disorders clinic, 19% had a potentially reversible cause of the cognitive impairment and 23% had a potentially reversible concomitant condition. The three most common potentially reversible diagnoses were depression, hydrocephalus, and alcohol dependence (Table 365-1).

Subtle cumulative decline in episodic memory is a natural part of aging. This frustrating experience, often the source of jokes and humor, is referred to as benign forgetfulness of the elderly. Benign means that it is not so progressive or serious that it impairs reasonably successful and productive daily functioning, although the distinction between benign and more significant memory loss can be difficult to make. At age 85, the average person is able to learn and recall approximately one-half the number of items (e.g., words on a list) that he or she could at age 18. A cognitive problem that has begun to subtly interfere with daily activities is referred to as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). A sizeable proportion of persons with MCI will progress to frank dementia, usually caused by AD. The conversion rate from MCI to AD is ~12% per year. It remains unclear why some individuals show progression and others do not. Factors that predict progression from MCI to AD include a memory deficit >1.5 standard deviations from the norm, family history of dementia, the presence of an apolipoprotein 4 (Apo 4), and small hippocampal volumes. There is optimism that new positron emission tomography (PET) imaging techniquesthat label amyloid or tau in vivo might aid in early diagnosis of AD in the future.

The major degenerative dementias include AD, FTD and related disorders, DLB, HD, and prion disorders including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). These disorders are all associated with the abnormal aggregation of a specific protein: A42 in AD, tau or TDP-43 in FTD, - synuclein in DLB, polyglutamine repeats in HD, and prions in CJD (Table 365-2).

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT:

Dementia

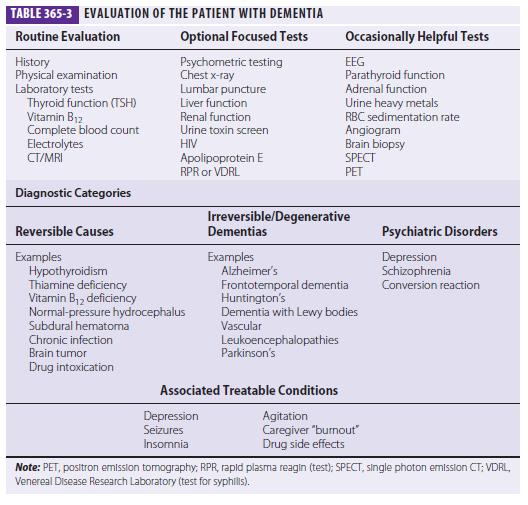

Three major issues should be kept in the forefront: (1) What is the most accurate diagnosis? (2) Is there a treatable or reversible component to the dementia? (3) Can the physician help to alleviate the burden on caregivers? A broad overview of the approach to dementia is shown in Table 365-3.

The major degenerative dementias can usually be distinguished by the initial symptoms; neuropsychological, neuropsychiatric, and neurologic findings; and neuroimaging features (Table 365-4).

HISTORY

The history should concentrate on the onset, duration, and tempo of progression of the dementia.

An acute or subacute onset of confusion may represent delirium and should trigger the search for intoxication, infection, or metabolic derangement. An elderly person with slowly progressive memory loss over several years is likely to suffer from AD. Nearly 75% of AD patients begin with memory symptoms, but other early symptoms include difficulty with managing money, driving, shopping, following instructions, finding words, or navigating.

A change in personality, disinhibition, and gain of weight or food obsession suggests FTD, not AD. FTD is also suggested by the finding of apathy, loss of executive function, or progressive abnormalities in speech, or by a relative sparing of memory or spatial abilities. The diagnosis of DLB is suggested by the early presence of visual hallucinations; parkinsonism; delirium; REM sleep disorder (the merging of dreamstates into wakefulness); or Capgras’ syndrome, the delusion that a familiar person has been replaced by an impostor.

A history of sudden stroke with irregular stepwise progression suggests multi-infarct dementia. Multiinfarct dementia is also commonly seen in the setting of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular

disease, and diabetes. In patients suffering from cerebrovascular disease, it can be difficult to determine whether the dementia is due to AD, multi-infarct dementia, or a mixture of the two as many of the risk factors for vascular dementia, including diabetes, high cholesterol, elevated homocysteine and low exercise, are also risk factors for AD. Rapid progression of the dementia in association with motor rigidity and myoclonus suggests CJD.

Seizures may indicate strokes or neoplasm.

Gait disturbance is commonly seen with multi-infarct dementia, PD, or normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH). Multiple sex partners or intravenous drug use should trigger a search for central nervous system (CNS) infection, especially for HIV.

A history of recurrent head trauma could indicate chronic subdural hematoma, dementia pugilistica, or NPH. Alcoholism may suggest malnutrition and thiamine deficiency. A remote history of gastric surgery resulting in loss of intrinsic factor can bring about vitamin B12 deficiency. Certain occupations such as working in a battery or chemical factory might indicate heavy metal intoxication.

Careful review of medication intake, especially of sedatives and tranquilizers, may raise the issue of chronic drug intoxication. A positive family of dementia is found in HD and in forms of familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD), FTD, or prion disorders.

The recent death of a loved one, or depressive signs such as insomnia or weight loss, raises the possibility of pseudodementia due to depression.

PHYSICAL AND NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION A thorough general and neurologic examination

is essential to document dementia, look for other signs of nervous system involvement, and search for clues suggesting a systemic disease that might be responsible for the cognitive disorder. AD does not affect motor systems until later in the course. In contrast, FTD patients often develop axial rigidity, supranuclear gaze palsy, or features of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). In DLB, initial symptoms may be the new onset of a parkinsonian syndrome (resting tremor, cogwheel rigidity, bradykinesia, festinating gait) with the dementia following later, or vice versa. Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is associated with dystonia, alien hand, and asymmetric extrapyramidal, pyramidal, or sensory deficits or myoclonus. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is associated with unexplained falls, axial rigidity, dysphagia, and vertical gaze deficits. CJD is suggested by the presence of diffuse rigidity, an akinetic state, and myoclonus.

Hemiparesis or other focal neurologic deficits may occur in multi-infarct dementia or brain tumor. Dementia with a myelopathy and peripheral neuropathy suggests vita-min B12 deficiency. A peripheral neuropathy could also indicate an underlying vitamin deficiency or heavy metal intoxication. Dry, cool skin, hair loss, and bradycardia suggest hypothyroidism. Confusion associated with repetitive stereotyped movements may indicate ongoing seizure activity. Hearing impairment or visual loss may produce confusion and disorientation misinterpreted as dementia. Such sensory deficits are common in the elderly but can be a manifestation of mitochondrial disorders.

COGNITIVE AND NEUROPSYCHIATRIC EXAMINATION Brief screening tools such as the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) help to confirm the presence of cognitive impairment and to follow the progression of dementia (Table 365-5). The MMSE, an easily administered 30-point test of cognitive function, contains tests of orientation, working memory (e.g., spell world backwards), episodic memory (orientation and recall), language comprehension, naming, and copying. In most patients with MCI and some with clinically apparent AD, the MMSE may be normal and a more rigorous set of neuropsychological tests will be required. Additionally, when the etiology for the dementia syndrome remains in doubt, a specially

tailored evaluation should be performed that includes tasks of working and episodic memory, frontal executive function, language, and visuospatial and perceptual abilities. In AD the deficits involve episodic memory, category generation (“name as many animals as you can in one minute”), and visuoconstructive ability.

Deficits in verbal or visual episodic memory are often the first neuropsychological abnormalities seen with AD, and tasks that require the patient to recall a long list of words or a series of pictures after a predetermined delay will demonstrate deficits in most AD patients.

In FTD, the earliest deficits often involve frontal executive or language (speech or naming) function. DLB patients have more severe deficits in visuospatial function but do better on episodic memory tasks than patients with AD. Patients with vascular dementia often demonstrate a mixture of frontal executive and visuospatial deficits.

In delirium, deficits tend to fall in the area of attention, working memory, and frontal function.

A functional assessment should also be performed. The physician should determine the day-to-day impact of the disorder on the patient’s memory, community affairs, hobbies, judgment, dressing, and eating. Knowledge of the patient’s day-to-day function will help the clinician and the family to organize a therapeutic approach.

Neuropsychiatric assessment is important for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. In the early stages of AD, mild depressive features, social withdrawal, and denial of illness are the most prominent psychiatric changes. However, patients often maintain their social skills into the middle stages of the illness, when delusions,

agitation, and sleep disturbance become more common. In FTD, dramatic personality change, apathy, overeating, repetitive compulsions, disinhibition, euphoria, and loss of empathy are common. DLB shows visual hallucinations, delusions related to personal identity, and day-to-day fluctuation. Vascular dementia can present with psychiatric symptoms such as depression, delusions, disinhibition, or apathy.

LABORATORY TESTS

The choice of laboratory tests in the evaluation of dementia is complex. The physician does not want to miss a reversible or treatable cause, yet no single etiology is common; thus, a screen must employ multiple tests, each of which has a low yield. Cost/benefit ratios are difficult to assess, and many laboratory screening algorithms for dementia discourage multiple tests. Nevertheless, even a test with only a 1–2% positive rate is probably worth undertaking if the alternative is missing a treatable cause of dementia. Table 365-3 lists most screening tests for dementia. Recently the American Academy of Neurology recommended the routine measurement of thyroid function, a vitamin B12 level test, and a neuroimaging study (CT or MRI).

Neuroimaging studies will identify primary and secondary neoplasms,locate areas of infarction, diagnose subdural hematomas, and suggest NPH or diffuse white matter disease. They also lend support to the diagnosis of AD, especially if there is hippocampal atrophy in addition to diffuse cortical atrophy. Focal frontal and/or anterior temporal atrophy suggests FTD. There is no specific pattern yet determined for DLB, although these patients tend to have less hippocampal atrophy than patients with AD. The use of diffusion- weighted imaging with MRI will detect abnormalities in the cortical ribbon and basal ganglia in the vast majority of patients with CJD. Large white-matter abnormalities correlate with a vascular etiology for dementia. The role of functional imaging in the diagnosis of dementia is still under study. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and PET scanning will show temporal- parietal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism in AD and frontotemporal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism in FTD, but most of these changes reflect atrophy. Recently, amyloid imaging has shown promise for the diagnosis of AD, and Pittsburgh Agent B appears to be a reliable agent for detecting brain amyloid due to the accumulation of A42 within plaques (Fig. 365-1). Similarly, MRI perfusion and brain activation studies using functional MRI are under active study as potential early diagnostic tools.

Lumbar puncture need not be done routinely in the evaluation of dementia, but it is indicated if CNS infection is a serious consideration.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of tau protein and A42 amyloid show differing patterns with the various dementias; however, the sensitivity and specificity of these measures are not sufficiently high to warrant routine measurement. Formal psychometric testing, though not necessary in every patient with dementia, helps to document the severity of dementia, suggest psychogenic causes, and provide a semiquantitative method for following the disease course. EEG is rarely helpful except to suggest CJD (repetitive bursts of diffuse high voltage sharp waves) or an underlying nonconvulsive seizure disorder (epileptiform discharges). Brain biopsy (including meninges) is not advised except to diagnose vasculitis, potentially treatable neoplasms, unusual infections, or systemic disorders such as vasculitis or sarcoid, or in young persons where the diagnosis is uncertain. Angiography should be considered when cerebral vasculitis is a possible cause of the dementia.

SPECIFIC DEMENTIAS

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Approximately 10% of all persons over the age of 70 have significant memory loss, and in more than half the cause is AD. It is estimated that the annual total cost of caring for a single AD patient in an advanced stage of the disease is >$50,000. The disease also exacts a heavy emotional toll on family members and caregivers. AD can occur in any decade of adulthood, but it is the most common cause of dementia in the elderly. AD most often presents with subtle onset of memory loss followed by a slowly progressive dementia that has a course of several years. Pathologically, there is diffuse atrophy of the cerebral cortex with secondary enlargement of the ventricular system. Microscopically, there are neuritic plaques containing A amyloid, silver-staining neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in neuronal cytoplasm, and accumulation of A42 amyloid in arterial walls of cerebral blood vessels (see “Pathogenesis,” below). The identification of four different susceptibility genes for AD has provided a foundation for rapid progress in understanding AD’s biologic basis.

Clinical Manifestations The cognitive changes with AD tend to follow a characteristic pattern, beginning with memory impairment and spreading to language and visuospatial deficits. However, ~20% of AD patients present with nonmemory complaints such as word-finding, organizational, or navigational difficulty. In the early stages of the disease, the memory loss may go unrecognized or be ascribed to benign forgetfulness. Once the memory loss begins to affect day-to-day activities or falls below 1.5 standard deviations from normal on standardized memory tasks, the disease is defined as MCI. Approximately 50%

of MCI individuals will progress to AD within 5 years. Slowly the cognitive problems begin to interfere with daily activities, such as keeping track of finances, following instructions on the job, driving, shopping, and housekeeping. Some patients are unaware of these difficulties (anosognosia), while others have considerable insight. Change of environment may be bewildering, and the patient may become lost on

walks or while driving an automobile. In the middle stages of AD, the patient is unable to work, is easily lost and confused, and requires daily supervision. Social graces, routine behavior, and superficial conversation may be surprisingly intact. Language becomes impaired—first naming, then comprehension, and finally fluency. In some patients, aphasia is an early and prominent feature. Word-finding difficulties

and circumlocution may be a problem even when formal testing demonstrates intact naming and fluency. Apraxia emerges, and patients have trouble performing sequential motor tasks. Visuospatial deficits begin to interfere with dressing, eating, solving simple puzzles, and copying geometric figures. Patients may be unable to do simple calculations or tell time.

In the late stages of the disease, some persons remain ambulatory but wander aimlessly. Loss of judgment, reason, and cognitive abilities is inevitable. Delusions are common and usually simple in quality, such as delusions of theft, infidelity, or misidentification. Approximately 10% of AD patients develop Capgras’ syndrome, believing that a caregiver has been replaced by an impostor. In contrast to DLB, where Capgras’ syndrome is an early feature, in AD this syndrome emerges later in the course of the illness. Loss of inhibitions and aggression may occur and alternate with passivity and withdrawal. Sleep-wake patterns are prone to disruption, and nighttime wandering becomes disturbing to the household.

Some patients develop a shuffling gait with generalized muscle rigidity associated with slowness and awkwardness of movement. Patients often look parkinsonian (Chap. 366) but rarely have a rapid, rhythmic, resting tremor. In endstage AD, patients become rigid, mute, incontinent, and bedridden. Help may be needed with the simplest tasks, such as eating, dressing, and toilet function.

They may show hyperactive tendon reflexes.

Myoclonic jerks (sudden brief contractions of various muscles or the whole body) may occur spontaneously

or in response to physical or auditory stimulation. Myoclonus raises the possibility of CJD (Chap. 378), but the course of AD is much more prolonged. Generalized seizures may also occur. Often death results from malnutrition, secondary infections, pulmonary emboli, or heart disease. The typical duration of AD is 8–10 years, but the course can range from 1 to 25 years. For unknown reasons, some AD patients

show a steady downhill decline in function, while others have prolonged plateaus without major deterioration.

Differential Diagnosis

Early in the disease course, other etiologies of dementia should be excluded. These include treatable entities such as thyroid disease, vitamin deficiencies, brain tumor, drug and medication intoxication, chronic infection, and severe depression (pseudodementia).

Neuroimaging studies (CT and MRI) do not show a single specific pattern with AD and may be normal early in the course of the disease. As AD progresses, diffuse cortical atrophy becomes apparent, and MRI scans show atrophy of the hippocampus (Fig. 365-2A, B).

Imaging helps to exclude other disorders, such as primary and secondary neoplasms, multi-infarct dementia, diffuse white matter disease, and NPH; it also helps to distinguish AD from other degenerative disorders with distinctive imaging patterns such as FTD or CJD. Functional imaging studies in AD reveal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism in the posterior temporal-parietal cortex (Fig. 365-2C, D). The EEG in AD is normal or shows nonspecific slowing. Routine spinal fluid examination is also normal. CSF A amyloid levels are reduced, whereas levels of tau protein are increased, but the considerable overlap of these levels with those of the normal aged population limits the usefulness of these measurements in diagnosis. The use of blood Apo genotyping is discussed under “Pathogenesis,” below. Slowly progressive decline in memory and orientation, normal results on laboratory tests, and an MRI or CT scan showing only diffuse or posteriorly predominant cortical and hippocampal atrophy is highly suggestive of AD. A clinical diagnosis of AD reached after careful evaluation is confirmed at autopsy about 90% of the time, with misdiagnosed cases usually representing one of the other dementing disorders described later in this chapter, a mixture of AD with vascular pathology, or DLB.

Relatively simple clinical clues are useful in the differential diagnosis.

Early prominent gait disturbance with only mild memory loss suggests vascular dementia or, rarely, NPH (see below). Resting tremor with stooped posture, bradykinesia, and masked facies suggest PD (Chap. 366). The early appearance of parkinsonian features, visual hallucinations, delusional misidentification, or REM sleep disorder suggest DLB. Chronic alcoholism should prompt the search for vitamin deficiency. Loss of sensibility to position and vibration stimuli accompanied by Babinski responses suggests vitamin B12 deficiency (Chap. 372). Early onset of a seizure suggests a metastatic or primary brain neoplasm (Chap. 374). A past history of depression suggests pseudodementia (see below). A history of treatment for insomnia, anxiety, psychiatric disturbance, or epilepsy suggests chronic drug intoxication. Rapid progression over a few weeks or months associated with rigidity and myoclonus suggests CJD (Chap. 378). Prominent behavioral changes with intact memory and lobar atrophy on brain imaging are typical of FTD. A positive family history of dementia suggests either one of the familial forms of AD or one of the other genetic disorders associated with dementia, such as HD (see below), FTD (see below), familial forms of prion diseases (Chap. 378), or rare forms of hereditary ataxias (Chap. 368).

Epidemiology

The most important risk factors for AD are old age and a positive family history. The frequency of AD increases with each decade of adult life, reaching 20–40% of the population over the age of 85. A positive family history of dementia suggests a genetic cause of AD. Female gender may also be a risk factor independent of the greater longevity of women. Some AD patients have a past history of head trauma with concussion, but this appears to be a relatively minor risk factor. AD is more common in groups with very low educational attainment, but education influences test-taking ability, and it is clear that AD can affect persons of all intellectual levels. One study found that the capacity to express complex written language in early adulthood correlated with a decreased risk for AD. Numerous environmental factors, including aluminum, mercury, and viruses, have been proposed as causes of AD, but none has been demonstrated to play a significant role. Similarly, several studies suggest that the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents is associated with a decreased risk of AD, but this has not been confirmed in large prospective studies.

Vascular disease, in particular stroke, seems to lower the threshold forthe clinical expression of AD. Also, in many AD patients, amyloid angiopathy can lead to ischemic infarctions or hemorrhages. Diabetes increases the risk of AD threefold. Elevated homocysteine and cholesterol levels; hypertension; diminished serum levels of folic acid; low dietary intake of fruits, vegetables, and red wine; and low levels of exercise are all being explored as potential risk factors for AD. Pathology At autopsy, the most severe pathology is usually found in the hippocampus, temporal cortex, and nucleus basalis of Meynert (lateral septum). The most important microscopic findings are neuritic “senile” plaques and NFTs. These lesions accumulate in small numbers during normal aging of the brain but occur in excess in AD. There is increasing evidence to suggest that soluble amyloid fibrils called oligomers lead to the dysfunction of the cell and may be the first biochemical injury in AD. Misfolded A42 molecules may be the most toxic form of this protein. Accumulation of oligomers eventually leads to formation of neuritic plaques (Fig. 365-3).

The neuritic plaques contain a central core that includes A amyloid, proteoglycans, Apo 4, 1 antichymotrypsin, and other proteins. A amyloid is a protein of 39–42 amino acids that is derived proteolytically from a larger transmembrane protein named amyloid precursor protein (APP) when APP is cleaved by and secretases. The normal function of A amyloid is unknown. APP has neurotrophic and neuroprotective activities.

The plaque core is surrounded by the debris of degenerating neurons, microglia, and macrophages. The accumulation of A amyloid in cerebral arterioles is termed amyloid angiopathy. NFTs are silver-staining, twisted neurofilaments in neuronal cytoplasm that represent abnormally phosphorylated tau () protein and appear as paired helical filaments by electron microscopy. Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that may function to assemble and stabilize the microtubules that convey cell organelles, glycoproteins, and other important materials throughout the neuron. The ability of tau protein to bind to microtubule segments is determined partly by the number of phosphate groups attached to it. Increased phosphorylation of tau protein disturbs this normal process. Finally, the co-association of AD with DLB and vascular pathology is extremely common. Biochemically, AD is associated with a decrease in the cerebral cortical levels of several proteins and neurotransmitters, especially acetylcholine, its synthetic enzyme choline acetyltransferase, and nicotinic cholinergic receptors. Reduction of acetylcholine may be related in part to degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert that project to many areas of cortex. There is also reduction in norepinephrine levels in brainstem nuclei such as the locus coeruleus.

GENETIC CONSIDERATIONS

Several genetic factors play important roles in the pathogenesis of at least some cases of AD. One is the APP gene on chromosome 21. Adults with trisomy 21 (Down’s syn-drome) consistently develop the typical neuropathologic hallmarks of AD if they survive beyond age 40. Many develop a progressive dementia superimposed on their baseline mental retardation. APP is a membranespanning protein that is subsequently processed into smaller units, including A amyloid that is deposited in neuritic plaques. A peptide results from cleavage of APP by and secretases (Fig. 365-4).

Presumably the extra dose of the APP gene on chromosome 21 is the initiating cause of AD in adult Down’s syndrome and results in an excess of cerebral amyloid. Furthermore, a few families with early-onset FAD have been discovered to have point mutations in the APP gene. Although very rare, these families were the first examples of a single-gene autosomal dominant genetic transmission of AD.

Investigation of large families with multigenerational FAD led to the discovery of two additional AD genes, termed the presenilins. Presenilin-1 (PS- 1) is on chromosome 14 and encodes a protein called S182. Mutations in this gene cause an early-onset AD (onset before age 60 and often before age 50) transmitted in an autosomal dominant, highly penetrant fashion.

More than 100 different mutations have been found in the PS-1 gene in families from a wide range of ethnic backgrounds. Presenilin-2 (PS-2) is on chromosome 1 and encodes a protein called STM2. A mutation in the PS-2 gene was first found in a group of American families with Volga German ethnic background. Mutations in PS-1 are much more common than those in PS-2. The two genes (PS-1 and PS-2) are highly homologous and encode similar proteins that at first appeared to have seven transmembrane domains (hence the designation STM), but subsequent studies have suggested eight such domains, with a ninth submembrane region. Both S182 and STM2 are cytoplasmic neuronal proteins that are widely expressed throughout the nervous system. They are homologous to a cell-trafficking protein, sel 12, found in the nematode Coenorhabditis elegans. Patients with mutations in these genes have elevated plasma levels of A42 amyloid, and PS-1 mutations in cell cultures produce increased A42 amyloid in the media.

There is evidence that PS-1 is involved in the cleavage of APP at the gamma secretase site and mutations in either gene (PS-1 or APP) may disturb this function. Mutations in PS-1 have thus far proved to be the most common cause of early-onset FAD, representing perhaps 40–70% of this relatively rare syndrome. Mutations in PS-1 tend to produce AD with an earlier age of onset (mean onset 45 years) and a shorter, more rapidly progressive course (mean duration 6–7 years) than the disease caused by mutations in PS-2 (mean onset 53 years; duration 11 years). Some carriers of uncommon PS-2 mutations have had onset of dementia after the age of 70. Mutations in the presenilins are rarely involved in the more common sporadic cases of late-onset AD occurring in the general population. Molecular DNA blood testing for these uncommon mutations is now possible on a research basis, and mutation analysis of PS-1 is commercially available. Such testing is likely to be positive only in early-onset familial cases of AD. Any testing of asymptomatic persons at risk must be done in the context of formal, thoughtful genetic counseling.

A discovery of great importance has implicated the Apo gene on chromosome 19 in the pathogenesis of late-onset familial and sporadic forms of AD. Apo is involved in cholesterol transport (Chap. 350) and has three alleles: 2, 3, and 4. The Apo 4 allele has a strong association with AD in the general population, including sporadic and late-onset familial cases. Approximately 24–30% of the nondemented Caucasian population has at least one 4 allele (12–15% allele frequency), and about 2% are 4/4 homozygotes.

Approximately 40–65% of AD patients have at least one 4 allele, a highly significant difference compared with controls. On the other hand, many AD patients have no 4 allele, and individuals with 4 may never develop AD. Therefore, 4 is neither necessary nor sufficient as a cause of AD.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the Apo 4 allele, especially in the homozygous 4/4 state, is an important risk factor for AD. It appears to act as a dosedependent modifier of age of onset, with the earliest onset associated with the 4/4 homozygous state. It is unknown how Apo functions as a risk factor modifying age of onset, but it may be involved with the clearance of amyloid, less efficiently in the case of Apo 4. Apo is present in the neuritic amyloid plaques of AD, and it may also be involved in neurofibrillary tangle formation, because it binds to tau protein. Apo 4 decreases neurite outgrowth in cultures of dorsal root ganglion neurons, perhaps indicating a deleterious role in the brain’s response to injury. There is some evidence that the 2 allele may be “protective,” but that remains to be clarified. The use of Apo testing in the diagnosis of AD is controversial. It is not indicated as a predictive test in normal persons because its precise predictive value is unclear, and many individuals with the 4 allele never develop dementia. However, some cognitively normal 4 heterozygotes and homozygotes have been found by PET to have decreased cerebral cortical metabolic rates, suggesting possible presymptomatic abnormalities compatible with the earliest stage of AD. In demented persons who meet clinical criteria for AD, the finding of an 4 allele increases the reliability of diagnosis. However, the absence of an 4 allele does not eliminate the diagnosis of AD. Furthermore, all patients with dementia, including those with an 4 allele, require a search for reversible causes of their cognitive impairment. Nevertheless, Apo 4 remains the single most important biologic marker associated with risk for AD, and studies of its functional role and diagnostic usefulness are progressing rapidly. Its association (or lack thereof ) with other dementing illnesses needs to be fully evaluated. The 4 allele is not associated with FTD, DLB, or CJD. Additional genes are also likely to be involved in AD, but none have been reliably identified.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

The management of AD is challenging and gratifying, despite the absence of a cure or a robust pharmacologic treatment. The primary focus is on long-term amelioration of associated behavioral and neurologic problems.

Building rapport with the patient, family members, and other caregivers is essential to successful management. In the early stages of AD, memory aids such as notebooks and posted daily reminders can be helpful. Common sense and clinical studies show that family members should emphasize activities that are pleasant and deemphasize those that are unpleasant.

Kitchens, bathrooms, and bedrooms need to be made safe, and eventually patients must stop driving. Loss of independence and change of environment may worsen confusion, agitation, and anger. Communication and repeated calm reassurance are necessary. Caregiver “burnout” is common, often resulting in nursing home placement of the patient, and respite breaks for the caregiver help to maintain successful long-term management of the patient. Use of adult day-care centers can be most helpful. Local and national support groups, such as the Alzheimer’s Association, are valuable resources.

Donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, memantine, and tacrine are the drugs presently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of AD. Due to hepatotoxicity, tacrine is no longer used. The pharmacologic action of donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine is inhibition of cholinesterase, with a resulting increase in cerebral levels of acetylcholine.

Memantine appears to act by blocking overexcited N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) channels. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover studies with cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine have shown them to be associated with improved caregiver ratings of patients’ functioning and with an apparent decreased rate of decline in cognitive test scores over periods of up to 3 years. The average patient on an anticholinesterase

compound maintains his or her MMSE score for close to a year, whereas a placebo-treated patient declines 2–3 points over the same time period. Memantine, used in conjunction with cholinesterase inhibitors or by itself, seems to slow cognitive deterioration in patients with moderate to severe AD and is not approved for mild AD. These compounds have only modest efficacy for AD and offer even less benefit in the late stages.

All the cholinesterase inhibitors are relatively easy to administer, and their major side effects are gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, diarrhea, cramps), altered sleep with bad dreams, bradycardia (usually benign), and sometimes muscle cramps.

In a prospective observational study, the use of estrogen replacement therapy appeared to protect—by about 50%—against development of AD in women. This study seemed to confirm the results of two earlier casecontrolled studies. Sadly, a prospective placebo-controlled study of a combined estrogen-progesterone therapy for asymptomatic postmenopausal women increased, rather than decreased, the prevalence of dementia. This study markedly dampened enthusiasm for hormone treatments for the prevention of dementia. Additionally, no benefit has been found in the treatment of AD with estrogen.

In patients with moderately advanced AD, a prospective trial of the antioxidants selegiline (Chap. 366), -tocopherol (vitamin E), or both, slowed institutionalization and progression to death. Because vitamin E has less potential for toxicity than selegiline and is cheaper, the doses used in this study of 1000 IU twice daily are offered to many patients with AD. However, the beneficial effects of vitamin E remain controversial, and most investigators no longer give it in these high doses because of potential cardiovascular complications.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of an extract of Ginkgo biloba found modest improvement in cognitive function in subjects with AD and vascular dementia. This study requires confirmation before Ginkgo biloba is used as a treatment for dementia because there was a high subject dropout rate and no improvement on a clinician’s judgment scale. A comprehensive 6-year multicenter prevention study using Ginkgo biloba is underway.

Vaccination against A42 has proved highly efficacious in mouse models of AD; it helped to clear amyloid from the brain and prevent further accumulation of amyloid. However, in human trials this approach led to life-threatening complications, including meningoencephalitis. Modifications of the vaccine approach using passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies are currently being evaluated in phase 3 trials. Another experimental approach to the treatment of AD has been the use of and secretase inhibitors that diminish the production of A42. Several retrospective studies suggest that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) may have a protective effect on dementia, and controlled prospective studies are being conducted. Similarly, prospective studies with the goal of lowering serum

homocysteine levels are underway, suggesting an association of elevated homocysteine with dementia progression based on epidemiologic studies.

Finally, there is now a strong interest in the relationship between diabetes and AD, and insulin-regulating studies are being conducted.

Mild to moderate depression is common in the early stages of AD and responds to antidepressants or cholinesterase inhibitors. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly used due to their low anticholinergic side effects. Generalized seizures should be treated with an appropriate anticonvulsant, such as phenytoin or carbamazepine. Agitation, insomnia, hallucinations, and belligerence are especially troublesome characteristics of some AD patients, and these behaviors can lead to nursing home placement. The newer generation of atypical antipsychotics, such as risperidone, quetiapine, and olanzapine, are being used in low doses to treat these neuropsychiatric symptoms. The few controlled studies comparing drugs against behavioral intervention in the treatment of agitation suggest mild efficacy with significant side effects related to sleep, gait, and cardiovascular complications. All of the antipsychotics carry a blackbox warning and should be used with caution. However, careful, daily, nonpharmacologic behavior management is often not available, rendering medications necessary.

VASCULAR DEMENTIA

Dementia associated with cerebral vascular disease can be divided into two general categories: multi-infarct dementia and diffuse white matter disease (also called leukoaraiosis, subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy or Binswanger’s disease). Cerebral vascular disease appears to be a more common cause of dementia in Asia than in Europe and North America. Individuals who have had several strokes may develop chronic cognitive deficits, commonly called multi-infarct dementia.

The strokes may be large or small (sometimes lacunar) and usually involve several different brain regions. The occurrence of dementia depends partly on the total volume of damaged cortex, but it is also more common in individuals with left-hemisphere lesions, independent of any language disturbance. Patients typically report a history of discrete episodes of sudden neurologic deterioration. Many multi-infarct dementia patients have a history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or other manifestations of widespread atherosclerosis.

Physical examination usually shows focal neurologic deficits such as hemiparesis, a unilateral Babinski reflex, a visual field defect, or pseudobulbar palsy. Recurrent strokes result in a stepwise progression of disease. Neuroimaging studies show multiple areas of infarction.

Thus, the history and neuroimaging findings differentiate this condition from AD. However, both AD and multiple infarctions are common and sometimes occur together. With normal aging, there is also an accumulation of amyloid in cerebral blood vessels, leading to a condition called cerebral amyloid angiopathy of aging (not associated with dementia), which predisposes older persons to hemorrhagic lobar stroke. AD patients with amyloid angiopathy may be at increased risk for cerebral infarction.

Some individuals with dementia are discovered on MRI to have bilateral abnormalities of subcortical white matter, termed diffuse white matter disease, often occurring in association with lacunar infarctions (Fig. 365-5).

The dementia may be insidious in onset and progress slowly, features that distinguish it from multi-infarct dementia, but other patients show a stepwise deterioration more typical of multi-infarct dementia. Early symptoms are mild confusion, apathy, changes in personality, depression, psychosis, memory, and spatial or executive deficits. Marked difficulties in judgment and orientation and dependence on others for daily activities develop later. Euphoria, elation, depression, or aggressive behaviors are common as the disease progresses.

Both pyramidal and cerebellar signs may be present in the same patient.

A gait disorder is present in at least half of these patients. With advanced disease, urinary incontinence and dysarthria with or without other pseudobulbar features (e.g., dysphagia, emotional lability) are frequent. Seizures and myoclonic jerks appear in a minority of patients.

This disorder appears to result from chronic ischemia due to occlusive disease of small, penetrating cerebral arteries and arterioles (microangiopathy).

Any disease-causing stenosis of small cerebral vessels may be the critical underlying factor, though most typically hypertension is the main cause. The term Binswanger’s disease should be used with caution, because it does not really identify a single entity.

Other rare causes of white matter disease also present with dementia, such as adult metachromatic leukodystrophy (arylsulfatase A deficiency) and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (papovavirus infection). A dominantly inherited form of diffuse white matter disease is known as cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Clinically, there is a progressive dementia developing in the fifth to seventh decades in multiple family members who may also have a history of migraine and recurrent stroke without hypertension. Skin biopsy may show characteristic dense bodies in the media of arterioles. The disease is caused by mutations in the notch 3 gene, and there is a commercially available genetic test. The frequency of this disorder is unknown, and there are no known treatments.

Mitochondrial disorders can present with strokelike episodes and can selectively injure basal ganglia or cortex. Many such patients show other findings suggestive of a neurologic or systemic disorder such as ophthalmoplegia, retinal degeneration, deafness, myopathy, neuropathy, or diabetes. Diagnosis is difficult but serum—especially CSF—levels of lactate and pyruvate may be abnormal, and biopsy of affected tissue is often diagnostic. Treatment of vascular dementia must be focused on the underlying causes, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, and diabetes. Recovery of lost cognitive function is not likely to occur, although fluctuations with periods of improvement are common. Anticholinesterase compounds are being studied as a treatment for vascular dementia.

FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA, PROGRESSIVE SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY, AND CORTICOBASAL DEGENERATION

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) often begins when the patient is in the fifth to seventh decades, and in this age group it is nearly as common as AD. Most studies suggest that FTD is twice as common in men as it is in women. Unlike AD, behavioral symptoms predominate in the early stages of FTD. Genetics play a significant role in a sizable minority of cases. The clinical heterogeneity in familial and sporadic forms of FTD is remarkable, with patients demonstrating variable mixtures of disinhibition, dementia, PSP, CBD, and motor neuron disease. The most common genetic mutations that cause an autosomal dominant form of FTD involve the tau or progranulin genes, both on chromosome 17. Tau mutations lead to a change in the alternate splicing of tau or cause loss of function in the tau molecule. With progranulin, a missense

mutation in the coding sequence of the gene is the underlying cause for the neurodegeneration. Progranulin appears to be a rare example of an autosomal dominant mutation leading to haploinsufficiency—too little of the progranulin protein. Both tau and progranulin mutations are associated with parkinsonian features, while ALS is rare in the setting of these mutations. In contrast, familial FTD with ALS has been linked to chromosome 9. Mutations in the valosin (chromosome 9) and ESCRTII molecules (chromosome 3) also lead to autosomal dominant forms of familial FTD. In FTD, early symptoms are divided among cognitive, behavioral, and sometimes motor abnormalities, reflecting degeneration of the anterior frontal and temporal regions, basal ganglia, and motor neurons. Cognitive testing typically reveals spared memory but impaired planning, judgment, o language. Poor business decisions and difficulty organizing work tasks are common, and speech and language deficits often emerge. Patients with FTD often show an absence of insight into their condition. Common behavioral deficits include apathy, disinhibition, weight gain, food fetishes, compulsions, and euphoria.

Findings at the bedside are dictated by the anatomic localization of the disorder. Asymmetric left-frontal cases present with nonfluent aphasias, while left anterior temporal degeneration is characterized by loss of words and concepts related to language (semantic dementia). Nonfluent patients quickly progress to mutism, while those with semantic dementia develop features of multimodality agnosia, losing the ability to recognize faces, objects, words, and the emotions of others. Copying, calculating, and navigation often remain normal into later in the illness. Recently it has become apparent that many if not most patients with nonfluent aphasia progress to clinical syndromes that overlap with PSP and CBD and show these pathologies at autopsy. This left-hemisphere presentation of FTD has been called primary progressive aphasia. In contrast, right-frontal or temporal cases show profound alterations in social conduct, with loss of empathy, disinhibition, and antisocial behaviors predominating. Memory and visuospatial skills are relatively spared in most FTD patients. There is a striking overlap among FTD, PSP, CBD, and motor neuron disease; ophthalmoplegia, dystonia, swallowing symptoms, and fasciculations are common at presentation of FTD or emerge during the course of the illness.

The distinguishing anatomic hallmark of FTD is a marked lobar atrophy of temporal and/or frontal lobes, which can be visualized by neuroimaging studies and is readily apparent at autopsy (Figs. 365-6 and 365-7).

The atrophy is sometimes asymmetric and may involve the basal ganglia. Two major pathologies have been linked to the clinical syndrome, one associated with tau inclusions, the other with inclusions that stain negatively for tau but positively for ubiquitin and TDP-43. Microscopic findings that are seen across all FTD cases include gliosis, neuronal loss, and spongiosus.

Approximately one-half of all cases show swollen or ballooned neurons containing cytoplasmic inclusions that stain positively for tau.

These aggregates sometimes resemble those found in PSP and CBD, and tau plays a major role in the pathogenesis of all three conditions. A toxic gain of function related to tau underlies the pathogenesis of many familial cases and is presumed to be a factor in sporadic cases as well. Nearly 80% of FTD patients show involvement of the basal ganglia at autopsy, and 15% go on to develop motor neuron disease, underscoring the multisystem nature of this illness. Serotonergic losses are seen in many patients, and glutaminergic neurons are depleted. In

contrast to AD, the cholinergic system is relatively spared in FTD,

whereas serotonergic and glutaminergic neurons are depleted in many

patients.

Historically, Pick’s disease was described as a progressive degenerative

disorder characterized clinically by selective involvement of the

anterior frontal and temporal neocortex and pathologically by intracellular

inclusions (Pick bodies). Classic Pick bodies stain positive with

silver (argyrophilic) and tau, but many of the tau-positive inclusions

in FTD cases are not labeled with silver stains (Fig. 365-8).

Although the nomenclature for these patients has remained controversial, the term FTD is increasingly used to describe the clinical syndrome, while Pick’s disease is used to classify patients in whom the pathology shows classic Pick bodies (only a minority of patients with the clinical features of FTD).

The burden on caregivers of FTD patients is extremely high. Treatment is symptomatic, and there are currently no therapies known to slow progression or improve cognitive symptoms. Many of the behaviors that accompany FTD, such as depression, hyperorality, compulsions, and irritability, can be ameliorated with serotonin-modifying antidepressants. The co-association with motor disorders necessitates the careful use of antipsychotics, which can exacerbate this problem.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a degenerative disease that involves the brainstem, basal ganglia, and neocortex. Clinically, this disorder begins with falls and vertical supranuclear gaze paresis and progresses to symmetrical rigidity and dementia. A stiff, unstable posture with hyperextension of the neck and slow gait with frequent falls is characteristic of PSP. Early in the disease, patients have difficulty with downgaze and lose vertical opticokinetic nystagmus on downward movement of a target. Frequent unexplained and sometimes spectacular falls are common secondary to a combination of axial rigidity, inability to look down, and bad judgment. Although the patients have very limited voluntary eye movements, their eyes still retain oculocephalic reflexes (doll’s head maneuver); thus, the eye-movement

disorder is supranuclear. The dementia is similar to FTD with apathy, frontal/executive dysfunction, poor judgment, slowed thought processes, impaired verbal fluency, and difficulty with sequential actions and with shifting from one task to another all common at the time of presentation and often preceding the motor syndrome. Some patients begin with a nonfluent aphasia and progress to classical PSP.

There is only a limited response to L-dopa; no other effective treatments exist. Death occurs within 5–10 years of onset. At autopsy, abnormal accumulation of tau is found within neurons and glia, often in the form of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). These tangles are found in multiple subcortical structures (including the subthalamus, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, locus coeruleus, periaqueductal gray, superior colliculi, and oculomotor nuclei) as well as in the neocortex. The NFTs have similar staining characteristics to those of AD, but on electron microscopy they are generally seen to consist of straight tubules rather than the paired helical filaments found in AD.

In addition to its overlap with FTD and CBD (see below), PSP is often confused with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD). Although elderly Parkinson’s patients may have some difficulty with upgaze, they do not

develop downgaze paresis or other abnormalities of voluntary eye movements typical of PSP. Dementia does occur in ~20% of PD patients, often secondary to DLB. Furthermore, the behavioral syndromes seen with DLB differ from PSP (see below). The occurrence of dementia in PD is more likely with increasing age, increasing severity of extrapyramidal signs, a long duration of disease, and the presence of depression.

These patients also show cortical atrophy on brain imaging. Neuropathologically, there may be Alzheimer changes in the cortex (amyloid plaques and NFTs), neuronal Lewy body inclusions in both the substantia nigra and the cortex, or no specific microscopic changes other than gliosis and neuronal loss. Progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson’s disease are discussed in detail in Chap. 366.

Cortical basal degeneration (CBD) is a slowly progressive dementing illness associated with severe gliosis and neuronal loss in both the neocortex and basal ganglia (substantia nigra and striatum). Occasionally there is a unilateral onset with rigidity, dystonia, and apraxia of one arm and hand, sometimes called the alien hand, while in other instances the disease presents as a progressive frontal syndrome or as progressive symmetrical parkinsonism. Some patients begin with a progressive nonfluent aphasia or a progressive motor disorder of speech. Eventually CBD becomes bilateral and leads to dysarthria, slow gait, action tremor, and dementia. The microscopic features include enlarged, achromatic neurons in the cortex with tau inclusions. Glial plaques with tau inclusions are pathognomonic of CBD. The condition is rarely familial, the cause is unknown, and there is no specific treatment.

DEMENTIA WITH LEWY BODIES

The parkinsonian dementia syndromes are under increasing study, with many cases unified by the presence of Lewy bodies in both the substantia nigra and the cortex at pathology. The clinical syndrome is characterized by visual hallucinations, parkinsonism, fluctuating alertness, falls, and often REM sleep behavior disorder. Dementia can precede or follow the appearance of parkinsonism. Hence, one pathway to DLB occurs in patients with longstanding PD without cognitive impairment who slowly develop a dementia that is associated with visual hallucinations, parkinsonism, and fluctuating alertness. In others, the dementia and neuropsychiatric syndrome precede the parkinsonism. DLB patients are highly susceptible to metabolic perturbations, and in some patients the first manifestation of illness is a delirium, often precipitated by an infection or other systemic disturbance. A delirium induced by L-dopa, prescribed for parkinsonian

symptoms attributed to PD, may be the initial clue that the correct diagnosis is DLB. Even without an underlying precipitant, fluctuations can be marked in DLB patients, with the occurrence of episodic confusion admixed with lucid intervals. However, despite the fluctuating pattern, the clinical features persist over a long period of time, unlike delirium, which resolves following correction of the underlying precipitant.

Cognitively, DLB patients tend to have relatively better memory but more severe visuospatial deficits than individuals with AD.

The key neuropathologic feature is the presence of Lewy bodies throughout the cortex, amygdala, cingulate cortex, and substantia nigra.

Lewy bodies are intraneuronal cytoplasmic inclusions that stain with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and ubiquitin. They are composed of straight neurofilaments 7–20 nm long with surrounding amorphous material.

They contain epitopes recognized by antibodies against phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated neurofilament proteins, ubiquitin, and a presynaptic protein called -synuclein. Lewy bodies are traditionally found in the substantia nigra of patients with idiopathic PD. A profound cholinergic deficit is present in many patients with DLB and may be a factor responsible for the fluctuations and visual hallucinations present in

these patients. In patients without other pathologic features, the condition is referred to as diffuse Lewy body disease. In patients whose brains also contain excessive amounts of amyloid plaques and NFTs, the condition is called the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease. The quantity of Lewy bodies required to establish the diagnosis is controversial, but a definite diagnosis requires pathology. At autopsy, 10–30% of demented patients show cortical Lewy bodies.

Due to the overlap with AD and the cholinergic deficit in DLB, anticholinesterase compounds may be helpful. Exercise programs maximize the motor function of these patients. Similarly, antidepressants are often necessary to treat the depressive syndromes that accompany DLB. Atypical antipsychotics in low doses are sometimes needed to alleviate psychosis, although even low doses can increase extrapyramidal syndromes and may rarely lead to death. As noted above, patients with DLB are extremely sensitive to dopaminergic medications, which must be carefully titrated; tolerability may be improved by concomitant AD medications.

OTHER CAUSES OF DEMENTIA

Prion disorders such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) are rare conditions (~1 per million population) that produce dementia. CJD is a rapidly progressive disorder associated with dementia, focal cortical signs,

rigidity, and myoclonus, causing death in <1 year from the first symptoms.

The rapidity of progression seen with CJD is uncommon in AD so that distinction between the two disorders is usually possible. However, CBD and DLB, more rapid degenerative dementias with prominent abnormalities in movement, are more likely to be mistaken for CJD. The differential diagnosis for CJD usually includes other rapidly progressive

dementing conditions such as viral or bacterial encephalitides, Hashimoto’s encephalitis, CNS vasculitis, lymphoma, or paraneoplastic syndromes.

The markedly abnormal periodic EEG discharges and cortical and basal ganglia abnormalities on diffusion-weighted MRI are unique diagnostic features of CJD. Transmission from infected cattle to the human population in the United Kingdom has caused a small epidemic of atypical CJD in young adults. Prion diseases are discussed in detail in Chap. 378.

Huntington’s disease (HD) (Chap. 367) is an autosomal dominant, degenerative brain disorder. A DNA repeat expansion (CAG repeat) of the mutant gene on chromosome 4 forms the basis of a diagnostic blood test for the disease gene. The clinical hallmarks of the disease are chorea, behavioral disturbance, and frontal executive disorder. Onset is usually in the fourth or fifth decade, but there is a wide range in age of onset, from childhood to >70 years. Memory is frequently not impaired until late in the disease, but attention, judgment, awareness, and executive functions may be seriously deficient at an early stage.

Depression, apathy, social withdrawal, irritability, and intermittent disinhibition are common. Delusions and obsessive-compulsive behavior may occur. The disease duration is typically about 15 years but is quite variable. There is no specific treatment, but the adventitious movements may partially respond to first- and second-generation antipsychotics. Treatment of behavioral changes are discussed in “General Symptomatic Treatment of the Patient with Dementia,” below.

Asymptomatic adult children at risk for HD should receive careful genetic counseling prior to DNA testing, because a positive result may have serious emotional and social consequences.

Normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is a relatively uncommon syndrome with clinical, physiologic, and neuroimaging characteristics.

Historically, many of the individuals who have been treated for NPH have suffered from other dementias, particularly AD, multi-infarct dementia, and DLB. For NPH the clinical triad includes an abnormal gait (ataxic or apractic), dementia (usually mild to moderate), and urinary incontinence. Neuroimaging studies reveal enlarged lateralventricles (hydrocephalus) with little or no cortical atrophy. This syndrome is a communicating hydrocephalus with a patent aqueduct of Sylvius (Fig. 365-9), in contrast to congenital aqueductal stenosis, where the aqueduct is small. In many cases, periventricular edema is present. Lumbar puncture opening pressure is in the high normal range, and the CSF protein, sugar concentrations, and cell count are normal.

NPH is presumed to be caused by obstruction to normal flow of CSF over the cerebral convexity and delayed absorption into the venous system. The indolent nature of the process results in enlarged lateral ventricles but relatively little increase in CSF pressure. There is presumed stretching and distortion of white matter tracts in the corona radiata, but the exact physiologic cause of the clinical syndrome is unclear. Some patients have a history of conditions producing scarring of the basilar meninges (blocking upward flow of CSF) such as previous meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or head trauma. Others with longstanding but asymptomatic congenital hydrocephalus may have adult-onset deterioration in gait or memory that is confused with NPH. In contrast to AD, the NPH patient has an early and prominent gait disturbance and no evidence of cortical atrophy on CT or MRI. A number of attempts have been made to use various special studies to improve the diagnosis of NPH and predict the success of ventricular shunting. These include radionuclide cisternography (showing a delay in CSF absorption over the convexity) and various attempts to monitor and alter CSF flow dynamics, including a constant-pressure infusion test. None has proven to be specific or consistently useful. There is sometimes a transient improvement in gait or cognition following lumbar puncture (or serial punctures) with removal of 30–50 mL of CSF, but this finding also has not proven to be consistently predictive of post-shunt improvement. AD often masquerades as NPH, because the gait may be abnormal in AD and cortical atrophy sometimes is difficult to determine by CT or MRI early in the disease. Hippocampal atrophy on MRI is a clue favoring AD. Approximately 30–50% of patients identified by careful diagnosis as having NPH will show improvement with a ventricular shunting procedure. Gait may improve more than memory. Transient, short-lasting improvement is common.

Patients should be carefully selected for this operation, because subdural hematoma and infection are known complications. Dementia can accompany chronic alcoholism (Chap. 387). This may be a result of associated malnutrition, especially of B vitamins and particularly thiamine. However, other poorly defined aspects of chronic alcohol ingestion may also produce cerebral damage. A rare idiopathic syndrome of dementia and seizures with degeneration of the corpus callosum has been reported primarily in male Italian drinkers of red wine (Marchiafava-Bignami disease).

Thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency causes Wernicke’s encephalopathy (Chap. 269). The clinical presentation is a malnourished individual (frequently but not necessarily alcoholic) with confusion, ataxia, and diplopia from ophthalmoplegia. Thiamine deficiency damages the thalamus, mammillary bodies, midline cerebellum, periaqueductal grey matter of the midbrain, and peripheral nerves. Damage to the dorsomedial thalamic region correlates most closely with the memory loss. Prompt administration of parenteral thiamine (100 mg intravenously for 3 days followed by daily oral dosage) may reverse the disease if given in the first days of symptom onset. However, prolonged untreated thiamine deficiency can result in an irreversible dementia/ amnestic syndrome (Korsakoff ’s psychosis) or even death.

In Korsakoff ’s syndrome, the patient is unable to recall new information despite normal immediate memory, attention span, and level of consciousness. Memory for new events is seriously impaired, whereas memory of knowledge prior to the illness is relatively intact. Patients are easily confused, disoriented, and incapable of recalling new information for more than a brief interval. Superficially, they may be conversant, entertaining, and able to perform simple tasks and follow immediate commands. Confabulation is common, although not always present, and may result in obviously erroneous statements and elaborations. There is no specific treatment because the previous thiamine deficiency has produced irreversible damage to the medial thalamicnuclei and mammillary bodies. Mammillary body atrophy may be visible on high-resolution MRI (see Fig. 269-8).

Vitamin B12 deficiency, as can occur in pernicious anemia, causes a macrocytic anemia and may also damage the nervous system (Chaps. 100 and 372). Neurologically, it most commonly produces a spinal cord syndrome (myelopathy) affecting the posterior columns (loss of position and vibratory sense) and corticospinal tracts (hyperactive tendon reflexes with Babinski responses); it also damages peripheral nerves, resulting in sensory loss with depressed tendon reflexes. Damage to cerebral myelinated fibers may also cause dementia. The mechanism of neurologic damage is unclear but may be related to a deficiency of Sadenosylmethionine (required for methylation of myelin phospholipids) due to reduced methionine synthase activity or accumulation of methylmalonate, homocysteine, and propionate, providing abnormal substrates for fatty acids synthesis in myelin. The neurologic signs of vitamin B12 deficiency are usually associated with macrocytic anemia but on occasion may occur in its absence. Treatment with parenteral vitamin B12 (1000 g intramuscularly daily for a week, weekly for a month, and monthly for life for pernicious anemia) stops progression of the disease if instituted promptly, but reversal of advanced nervous system damage will not occur. Deficiency of nicotinic acid (pellagra) is associated with sun-exposed skin rash, glossitis, and angular stomatitis (Chap. 71). Severe dietary deficiency of nicotinic acid along with other B vitamins such as pyridoxine may result in spastic paraparesis, peripheral neuropathy, fatigue, irritability, and dementia. This syndrome has been seen in prisoner-of-war and concentration camps. Low serum folate levels appear to be a rough index of malnutrition, but isolated folate deficiency has not been proven to be specific cause of dementia. Infections of the CNS usually cause delirium and other acute neurologic syndromes (Chap. 269). However, some chronic CNS infections, particularly those associated with chronic meningitis (Chap. 377), may produce a dementing illness. The possibility of chronic infectious meningitis should be suspected in patients presenting with a dementia or behavioral syndrome who also have headache, meningismus, cranial neuropathy, and/or radiculopathy.

Between 20 and 30% of patients in the advanced stages of infection with HIV become demented (Chap. 182). Cardinal features include psychomotor retardation, apathy, and impaired memory.

This syndrome may result from secondary opportunistic infections but can also be caused by direct infection of CNS neurons with HIV. CNS syphilis (Chap. 162) was a common cause of dementia in the preantibiotic era; it is uncommon nowadays but can still be encountered in patients with multiple sex partners. Characteristic CSF changes consist of pleocytosis, increased protein, and a positive venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. Primary and metastatic neoplasms of the CNS (Chap. 374) usually produce focal neurologic findings and seizures rather than dementia.

However, if tumor growth begins in the frontal or temporal lobes, the initial manifestations may be memory loss or behavioral changes. A paraneoplastic syndrome of dementia associated with occult carcinoma (often small cell lung cancer) is termed limbic encephalitis (Chap. 97). In this syndrome, confusion, agitation, seizures, poor memory, movement disorders, and frank dementia may occur in association with sensory neuropathy.

A nonconvulsive seizure disorder may underlie a syndrome of confusion, clouding of consciousness, and garbled speech. Psychiatric disease is often suspected, but an EEG demonstrates the seizure discharges. If recurrent or persistent, the condition may be termed complex partial status epilepticus. The cognitive disturbance often responds to anticonvulsant therapy. The etiology may be previous small strokes or head

trauma; some cases are idiopathic. It is important to recognize systemic diseases that indirectly affect the brain and produce chronic confusion or dementia. Such conditions include hypothyroidism; vasculitis; and hepatic, renal, or pulmonary disease.

Hepatic encephalopathy may begin with irritability and confusion and slowly progress to agitation, lethargy, and coma (Chap. 268).

Isolated vasculitis of the CNS (CNS granulomatous vasculitis) (Chaps. 319 and 364) occasionally causes a chronic encephalopathy associated with confusion, disorientation, and cloudiness of consciousness. Headache is common, and strokes and cranial neuropathies may occur. Brain imaging studies may be normal or nonspecifically abnormal. CSF studies reveal a mild pleocytosis or elevation in the protein level. Cerebral

angiography often shows multifocal stenosis and narrowing of vessels. A few patients have only small-vessel disease that is not revealed on angiography.

The angiographic appearance is not specific and may be mimicked by atherosclerosis, infection, or other causes of vascular disease. Brain or meningeal biopsy demonstrates abnormal arteries with endothelial cell proliferation and infiltrates of mononuclear cells. The prognosis is often poor, although the disorder may remit spontaneously.

Some patients respond to glucocorticoids or chemotherapy.

Chronic metal exposure may produce a dementing syndrome. The key to diagnosis is to elicit a history of exposure at work or home, or even as a consequence of a medical procedure such as dialysis. Chronic lead poisoning from inadequately fired glazed pottery has been reported. Fatigue, depression, and confusion may be associated with episodic abdominal pain and peripheral neuropathy. Gray lead lines appear in the gums. There is usually an anemia with basophilic stippling of red cells. The clinical presentation can resemble that of acute intermittent porphyria, including elevated levels of urine porphyrins as a result of the inhibition of -aminolevulinic acid dehydrase. The treatment is chelation therapy with agents such as ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA). Chronic mercury poisoning produces dementia, peripheral neuropathy, ataxia, and tremulousness that may progress to a cerebellar intention tremor or choreoathetosis. The confusion and memory loss of chronic arsenic intoxication is also associated with nausea, weight loss, peripheral neuropathy, pigmentation and scaling of the skin, and transverse white lines of the fingernails (Mees’ lines). Treatment is chelation therapy with dimercaprol (BAL). Aluminum poisonin ghas been best documented with the dialysis dementia syndrome, in which water used during renal dialysis was contaminated with excessive

amounts of aluminum. This poisoning resulted in a progressive encephalopathy associated with confusion, nonfluent aphasia, memory loss, agitation, and, later, lethargy and stupor. Speech arrest and myoclonic jerks were common and associated with severe and generalized EEG changes. The condition has been eliminated by the use of deionized water for dialysis.

Recurrent head trauma in professional boxers may lead to a dementia sometimes called the “punch drunk” syndrome, or dementia pugilistica.

The symptoms can be progressive, beginning late in a boxer’s career or even long after retirement. The severity of the syndrome correlates with the length of the boxing career and number of bouts. Early in the condition, a personality change associated with social instability and sometimes paranoia and delusions occurs. Later, memory loss progresses to full dementia, often associated with parkinsonian signs and ataxia or intention tremor. At autopsy, the cerebral cortex may show changes similar to AD, although NFTs are usually more prominent than amyloid plaques (which are usually diffuse rather than neuritic).

There may also be loss of neurons in the substantia nigra.

Chronic subdural hematoma (Chap. 373) is also occasionally associated with dementia, often in the context of underlying cortical atrophy from conditions such as AD or HD. In these latter cases, evacuation of

subdural hematoma will not alter the underlying degenerative process.

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is characterized by the sudden onset of a severe episodic memory deficit, usually occurring in persons >50. Often the memory loss occurs in the setting of an emotional stimulus or physical exertion. During the attack, the individual is alert and communicative, general cognition seems intact, and there are no other neurologic signs or symptoms. The patient may seem confused and repeatedly ask about present events. The ability to form new memories returns after a period of hours, and the individual returns to normal with no recall for the period of the attack. Frequently no cause is determined, but cerebrovascular disease, epilepsy (7% in one study), migraine, or cardiac arrhythmias have all been implicated. A Mayo Clinic review of 277 patients with TGA found a past history of migraine in 14% and cerebrovascular disease in 11%, but these conditions were not temporally related to the TGA episodes. Approximately one-quarter of the patients had recurrent attacks, but they were not at increased risk for subsequent stroke. Rare instances of permanent memory loss after sudden onset have been reported, usually representing ischemic infarction of the hippocampi or medial thalamic nuclei bilaterally.